In less than a decade, Cloud Gate, known by most simply as “the Bean,” has vaulted into one of Chicago’s top attractions. The final product, a gleaming steel mirror that bends the Chicago sky and skyline around its surface, had a long path to fruition, from selection to development. This is the inside story on Chicago Bean history.

Choosing the Bean

Millennium Park, in some ways, is a misnomer. Planning for the project in a northwest corner of Grant Park began in 1997, but delays pushed its public unveiling to 2004, nearly half a decade after the transition into the 2000s. Nor were its costs as originally anticipated, rising from a substantial $150 million to $475 million by the time of completion. (Funds came from tax payers and private donors.)

Millennium Park, in some ways, is a misnomer. Planning for the project in a northwest corner of Grant Park began in 1997, but delays pushed its public unveiling to 2004, nearly half a decade after the transition into the 2000s. Nor were its costs as originally anticipated, rising from a substantial $150 million to $475 million by the time of completion. (Funds came from tax payers and private donors.)

Part of Millennium Park included plans for several public art works. A committee that included representatives from the Art Institute of Chicago, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, and some of the city’s foremost art patrons was tasked with narrowing the field and ultimately choosing the artists to tackle these public art installations.

To start, the committee pooled a list of 16–30 artists (the number varies based on accounts) from around the world with experience in large-scale outdoor works. Without soliciting specific ideas for the spaces in Millennium Park, the committee narrowed its list to just two artists: British artist Anish Kapoor and U.S. artist Jeff Koons.

With the field narrowed, the committee commissioned both artists for works in separate areas of Grant Park—Koons’ in AT&T Plaza (then known as Ameritech and later SBC Plaza) and Kapoor’s in the Lurie Garden. The initial proposal from Koons, however, quickly ran into challenges. Koons envisioned a 150-foot-long glass and steel slide raised 90 feet above the ground. Visitors would be able to observe the park from on high, then slide down to ground level. Yet to make the vision a reality, other components would be necessary, namely an elevator that could ensure access to the work for disabled visitors.

The physical size of the work, the committee also feared, could come to dominate the space. Reservations were in contrast to Kapoor’s proposal of a mirrored stainless steel object roughly 66 feet long. The only concern about Kapoor’s work, according to some, was that its location in the Lurie Garden might generate so much foot traffic as to trample the organic installations there. The solution was to move Kapoor’s unnamed project (Kapoor names projects only after their completion) to the space initially reserved for Koons. That space was also better suited to handle the 110-ton weight of the steel form. Koons’ project was scraped entirely.

The final decision, announced in 1999, budgeted just under $6 million for the project, with Ameritech contributing some $3 million. That optimistic estimate would be tripled before the final unveiling of Cloud Gate.

The Artist behind the Chicago Bean

Born in 1954 in Bombay (now Mumbai), India, Kapoor moved to London in the 1970s. He was a standout at Hornsey College of Art and Chelsea School of Art Design, and his reputation as one of the world’s leading sculptors has only grown. Kapoor has enjoyed solo exhibitions at some of art’s most respected venues, including the Guggenheim Museum in New York and Reina Sofia in Madrid, among many others. His works are housed in museums around the world, from San Francisco to Parto, Italy, and Sydney, Australia.

At the time of the Millennium Park proposal, Kapoor had yet to create a site-specific installation in the United States. His 1995 work Turning the World Inside Out, far smaller than the one proposed for Chicago, served as the conceptual basis for the polished metal work—a representation of liquid mercury, to some—that would become Cloud Gate.

“What I wanted to do,” Kapoor told the Chicago Tribune, “was to make a work that would deal with the incredible skyline of Chicago and the open sky and the lake but then also be a kind of gate. You know, the tradition of public sculpture is for the gate, the archway, the square to flow within [the landscape] rather than be an object decorating it.”

“Contemporary public spaces are a very difficult problem that we haven’t yet fully and properly understood,” Kapoor continued. “The idea here was to make a work that was drawing in the sky, the skyline and all of that, and at the same time allowing you to enter it like a piece of architecture that was pulling your own reflection into the fulcrum, making a kind of participatory experience.”

Creation of Cloud Gate

Creation of Cloud Gate lasted two years, spanning 2003 and 2004. The final steel shape reached 66 feet in length, 42 feet at its widest point, and rose as high as 33 feet. Its total cost—well above initial estimates—reached $23 million, with an array of donors picking up the difference.

Creation of Cloud Gate lasted two years, spanning 2003 and 2004. The final steel shape reached 66 feet in length, 42 feet at its widest point, and rose as high as 33 feet. Its total cost—well above initial estimates—reached $23 million, with an array of donors picking up the difference.

The long process began with a wooden model; that model transitioned into a digital image. The digital image, then, was sent to potential fabricators to create sample sheets of steel, the components that would eventually be welded together in a seamless finish. After seeking out three potential firms, Kapoor settled on Performance Structures, Inc., of Oakland, California. Its team had returned the highest quality sample to win the contract.

The company’s president, Ethan Silva, had learned of Kapoor’s work and his Chicago commission during a 1999 visit to London. There, he had had a conversation with a computer engineer who had worked with the artist on a prior project. At the time, most of Performance Structures’ work had been in boat building, a solid foundation for the skills needed to form precise yet gentle angles in steel plates. Still, Kapoor represented the company’s first collaboration with a major artist.

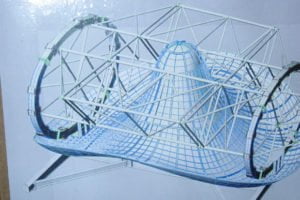

Before Performance Structures began forging the steel, Kapoor and Silva’s team spent six months in long-distance collaboration. The Performance Structures team sent milled foam models and accompanying computer versions to Kapoor, who would return feedback for another round of adjustments. These model plates of hard foam, each about 18 inches in length, served as the design framework for the 168 steel panels that were to comprise the final sculpture.

Before Performance Structures began forging the steel, Kapoor and Silva’s team spent six months in long-distance collaboration. The Performance Structures team sent milled foam models and accompanying computer versions to Kapoor, who would return feedback for another round of adjustments. These model plates of hard foam, each about 18 inches in length, served as the design framework for the 168 steel panels that were to comprise the final sculpture.

The final sheets, Silva explained, were essentially pieces of a steel eggshell: “It’s very thin but because it’s contiguous and smooth, it’s strong.” With final design for each plate established, Performance Structures manufactured each panel, polishing all to 98 percent of their final finishing.

Initial plans to ship the fully welded sculpture via ship—through the Panama Canal to the northeast U.S. coast and back across the St. Lawrence Seaway to Chicago—were scraped due to concerns about such a long journey with the one-of-kind work. Instead, individual plates were sent on trucks to Chicago, where final construction would take place. Edges would be welded together and re-polished to provide a seamless finish.

Initial plans to ship the fully welded sculpture via ship—through the Panama Canal to the northeast U.S. coast and back across the St. Lawrence Seaway to Chicago—were scraped due to concerns about such a long journey with the one-of-kind work. Instead, individual plates were sent on trucks to Chicago, where final construction would take place. Edges would be welded together and re-polished to provide a seamless finish.

More than a half-dozen workers built the interior rings and trusses—a steel skeleton—that supported the plates during construction and was removed after completion. The final work, true to its eggshell analogy, had no interior supports. Welding of plates took place under a tent to preserve the spectacle for its grand unveiling, which, unexpectedly, proved to be a recurring event.

The Bean Is Unveiled

The first, but not final, unveiling of the Chicago Bean occurred in July 2004 at the official opening of Millennium Park. However, not all seams had been yet been fully welded and polished. Kapoor was disappointed with the premature unveiling, wanting his work to reach the public eye only after all finishing touches were completed. Though the tent was intended to go back up following the initial festivities, the popularity of the Bean, which drew onlookers from early morning until late at night, convinced officials to hold off on finishing work until January 2005.

Work resumed in January and continued through August, when the tent again was removed. Still, the omphalos—the steel “navel” underneath Cloud Gate—didn’t receive its final polish until October, when the Bean attained its final form.

Work resumed in January and continued through August, when the tent again was removed. Still, the omphalos—the steel “navel” underneath Cloud Gate—didn’t receive its final polish until October, when the Bean attained its final form.

From its initial, partial unveiling to its present-day appearance, the Bean has captured the imagination of Chicagoans and visitors, becoming one of the must-see attractions of the city, even more so, perhaps, than any of the skyscrapers that curve gently in its brilliant reflection.

Like any work of art, Kapoor’s effort endured some criticism from those who felt it unimaginative. Yet public affection has turned even that critique on its head. The critical labeling of Cloud Gate as “The Electric Kidney Bean” served as genesis for the Chicago Bean, the moniker that has stuck, pulling Kapoor’s highest aspirations—some 80% of Cloud Gate reflects the Chicago sky—back down to earth for its millions of casual admirers.

Images courtesy of the Chicago Public Library.

“The Bean” is just one of many famous attractions home to Chicago. Visit The Clare and tour the area while you’re here. Call today to schedule a visit and be a tourist in our amazing city!