Dr. Sunil Shabde: Physics and Electrical Engineering Researcher Shares his Journey to the United States

Growing up in India, Clare resident Dr. Sunil Shabde was surrounded by science.

His father was a renowned mathematician, known for conducting research on Einstein’s Unified Field Theory in the 1930s. He inspired Sunil to pursue his own scientific passions.

After earning a degree in physics from Nagpur University and a degree in electrical engineering from the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore, Sunil struggled to find a job to his liking – one that would involve working with semiconductor devices, since they were developing at the time. He moved to the United States in 1963, where his journey truly began.

Life in the U.S.

Sunil knew moving to the U.S. would provide him with life-changing opportunities, but he felt guilty leaving his mother alone to care for his younger siblings. His father had died a few years prior, but his family ultimately encouraged him to leave.

So, Sunil married his childhood sweetheart and moved to the U.S. three months later on a student visa, having been accepted to Purdue University.

Upon stepping foot on Purdue’s campus, Sunil knew he made the right choice.

“Purdue, compared to India, was like a breath of fresh air,” he says.

There, he experienced a new level of academic freedom at his fingertips. Sunil wasn’t used to the idea that students could choose their own courses and career paths.

“My counselor said I could take as many courses as I wanted,” he says. “That was unheard of in India.”

In his home country, parents tended to choose careers for their children, and students typically followed a fixed curriculum, he says. He seized the freedom afforded to him at Purdue and enrolled in courses outside of the electrical engineering department.

“I took a quantum mechanics course that really thrilled me,” he says.

As he worked toward his master’s, his wife joined him in the United States, and he soon began envisioning where his career might take him. When he received his degree, a professor from Purdue who was given a promotion at Rice University offered Sunil an assistantship while he worked on his Ph.D. He felt hesitant, but his wife pushed him to accept the offer.

“She said, ‘Remember what you came here for. You came to do research, and if you take a job in some industry after your master’s, you won’t be able to do that,’” Sunil recalls. “That was the best advice she had ever given me.”

So, he accepted the assistantship, which only paid $250 a month. Sunil worked in a lab day and night, researching thermomagnetics, a new physics-related phenomenon for energy conversion.

While Sunil loved his work, the pay wasn’t sufficient, especially with a baby on the way. After his wife gave birth to their first-born daughter, Sunil didn’t know how they were going to cover the charges. Luckily, the doctor noticed that Sunil was working toward his Ph.D. and knew how very little he was earning. The doctor did the unthinkable for them.

“He waived all of my charges,” Sunil says. “I couldn’t believe it. I really got the sense that Americans are generous people.”

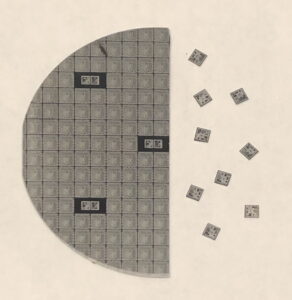

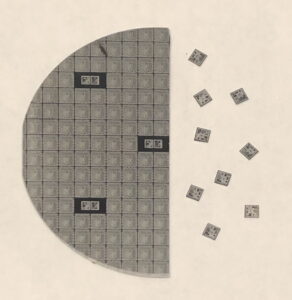

Within two years, he finished his Ph.D., becoming Dr. Sunil Shabde. He received a job offer to make microchips for Collins, known for its aviation and space electronics. The job took his family to Cedar Rapids, Iowa for six months, followed by Newport Beach, California, where he helped set up a microchip factory.

“I was also doing research, because they were setting up MOS technology that was way ahead of its time,” he says.

After working for Collins for over a year, Sunil felt the urge to pursue other opportunities. When the University of Michigan reached out to him to set up labs for students, where they could fabricate semiconductor devices and small chips, Sunil knew he had to jump in. As an assistant professor, he successfully established two labs and two courses for students to learn about recent developments in microchip technology.

“Students were lining up for registration, because who gets a chance in the university to see the fabrication of microchips?” he says.

Working in Silicon Valley

Again, Sunil realized that the real cutting-edge of technology was elsewhere, not in universities but in Silicon Valley.

He wanted to get involved with the early stage of the computer revolution. Sunil got a job in Silicon Valley, and he and his family made the move in 1973.

“I was basically chasing where the high technology was,” he says. “That was my main focus.”

Sunil spent more than 30 years working for several companies in Silicon Valley, including innovative startups. In that time, he witnessed many technological advancements.

“Before the microchips came, computers occupied the whole room,” he says. “Now we have laptops!”

Silicon Valley fostered a community of constant innovation. This allowed Sunil to research the new phenomena of the shrinking size of transistors.

He attended international conferences of the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers and published 10 papers on the hot electron effect alone. One of those papers, “Hot Electron-Induced Snapback Effect in MOS Transistors,” aimed to design protection for the microchips from electrostatic discharge. Even today, products depend on this idea. He also received six patents on alpha particle damage to chips in space.

“A lot of strange phenomenon happen when you shrink a transistor,” Sunil says. “We had to suppress harmful ones.”

To do so, he had to design innovative transistor structures within silicon.

During his time in Silicon Valley, Sunil worked on six generations of technology and transferred them to manufacturing. Over the course of his career, the number of transistors on a chip went from hundreds to several billion, while computer speed reached unprecedented gigahertz (GHz) range. This period saw the advent of internet, as well.

Today, Sunil feels proud to have participated in the microchip revolution from the beginning, a revolution that has propelled the United States to the forefront of this technology.

Life at The Clare

Sunil and his wife continued to live in California after their retirement in the 2000s. They raised two daughters, who are now in the prime of their careers. True to his academic urges, Sunil developed and taught courses in devices for industrial engineers, and he went on to write a biography about his father and his extensive research.

Through it all, Sunil says that he wouldn’t have excelled were it not for his wife by his side.

“She supported me in all of those moves,” he says. “She said, ‘I’ll go where your passion takes you.’ And after the kids grew up, she pursued her own career at Hewlett Packard as a computer software engineer.”

When his wife passed, Sunil’s daughters found The Clare and knew it would be perfect for him. Living here allows him to be closer to his daughters and freedom to pursue a newfound passion.

“I’m looking at the metaphysics side of philosophy,” he says. “I want to explore what’s beyond this world.”

As he reflects on his journey to the U.S. and the longevity of his career, Sunil knows it wasn’t easy.

“It was a struggle in the beginning, but it was very satisfying,” he says.