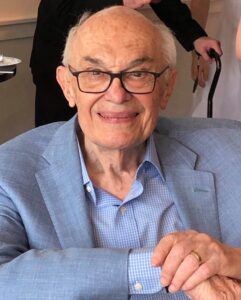

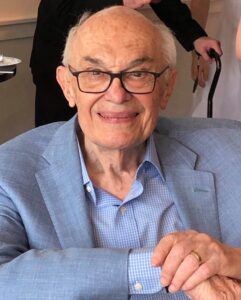

Andy Poznanski: One Step Ahead

Clare resident Andy Poznanski has often been one step ahead.

He and his family were one step ahead of significant danger on several occasions during World War II. He was a step ahead in certain aspects of pediatric radiology, including the development of approaches to reduce patient radiation exposure and the identification of genetic malformations.

Now, after a dramatic and challenging childhood and extensive career, Andy resides at The Clare in Chicago with his wife, Gail Margolis. They enjoy personalized service, excellent food and the company of wonderfully diverse and thoughtful residents.

“I’m not really in a hurry anymore to go anywhere,” he says. But throughout his life, that wasn’t always the case.

Evading World War II

As an 8-year-old in Poland when Germany attacked in September 1939, Andy joined his sister and parents in escaping to the east.

They left Warsaw with a horse and wagon days after the invasion, only to return when they heard Russia had also invaded Poland. His father believed it would be easier to get out of Poland from the German side. During this time, the family was caught between both warring parties and was subject to bombing and strafing on the roads.

“I recall how frightened we were fleeing first to the east, hiding in the forest, encountering German troops, and after returning to Warsaw, having our house searched by the Gestapo,” Andy says.

An uncle, who was the Consul General of Poland living in London with connections to various embassies, then arranged for a visa and false documents to enable the family to leave occupied Poland in February 1940. Andy was told that his family had one hour prior to boarding a train to Italy, and eventually to France. His father, a civil engineer, obtained a job working on a dam construction in Algeria, then a Department of France. However, no sooner had they arrived in Algiers that France fell to the Germans and the job ended. Fortunately, the funds advanced for their travel to the new job provided them with basic support despite severe rationing in the country.

Initially in Algeria, the German military presence was light, and life calmed down for Andy and his family. Andy attended school and learned French.

“I remember Algiers as being a lovely place to live,” Andy says.

Again one step ahead, just as the German presence began to increase dramatically, his father secured a job in Canada. The country sought engineers for the war effort. In July 1942, they traveled across the Atlantic Ocean on a Portuguese ship leased by an American Jewish organization to help refugees flee Europe. The ship unloaded its passengers in Baltimore, where they took a train to their new home in Canada – first Ottawa, then Montreal.

“I vividly remember landing in Baltimore and walking to the train with armed guards lining the path to make sure we didn’t escape into the United States,” Andy says.

This was in sharp contrast to the joyful reception they received upon arrival in Canada.

Embarking on a Career in Radiology

Andy attended McGill University in Montreal, studying mathematics and physics. Upon graduation, he decided to pursue medicine at McGill. This choice propelled him to become deeply involved in the emerging specialty of pediatric radiology, to engage in ongoing research, and later to become a member of the American Board of Radiology.

He obtained his U.S. citizenship and completed his residency at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit in 1960. Afterward, he remained on staff and set up a pediatric subsection within the department. Andy developed several devices to make X-ray procedures easier and more comfortable for children. Plus, he oversaw a significant expansion of the department.

From there, he became a Professor and Co-Director of Radiology at the Mott Children’s Hospital at the University of Michigan. After 11 years in Ann Arbor, Andy came to Chicago in 1979 as a Professor of Radiology at Northwestern University and Radiologist in Chief at Children’s Memorial Hospital 1979 (presently Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago). He was known there affectionately as “Dr. P.”

During these years, Andy not only shared his knowledge with future doctors. He was also recognized as an expert in radiology of the hand, particularly identifying symptoms of congenital malformations.

“Perhaps the most satisfying and enjoyable aspects of my career were interactions with clinical colleagues, as well as teaching residents and technologists,” Andy says.

Over the course of his career, Andy became president of three national and international professional organizations. He received four gold medals for contributions to radiology, frequently lecturing at conferences worldwide. Andy was also a member of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. Always involved in research, he authored three books, coauthored another and found time to publish more than 200 articles. His works centered on the radiology of the hand, growth and development, and congenital malformations.

His multi-decade career allowed him to experience tremendous change in the field of radiology.

“That’s the amazing thing, and that’s why it was so exciting,” Andy says. “When I first started, all we had were X-rays and wet film.”

Then, processing improved considerably, followed by the introduction of nuclear medicine and ultrasound. CT was the next major development, followed by MRI.

“All of a sudden, you could separate muscles, blood vessels, fat and more,” Andy says. “You saw anatomy so much better.”

Of course, these advancements kept Andy on his toes.

“I had a lot of learning to do,” he jokes.

Andy eased his way out of his career in radiology, retiring in Chicago as Chair of the department at age 68. He continued to work part-time for the next 12 years.

Through it all, from his flight from Europe to his challenging work life, Andy proved himself resilient, adaptive and modest.

“It was hard, of course,” Andy says. “But I was fortunately able to face difficult situations and deal with them.”